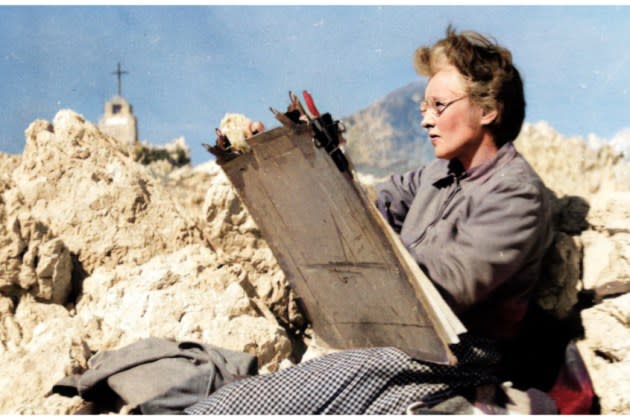

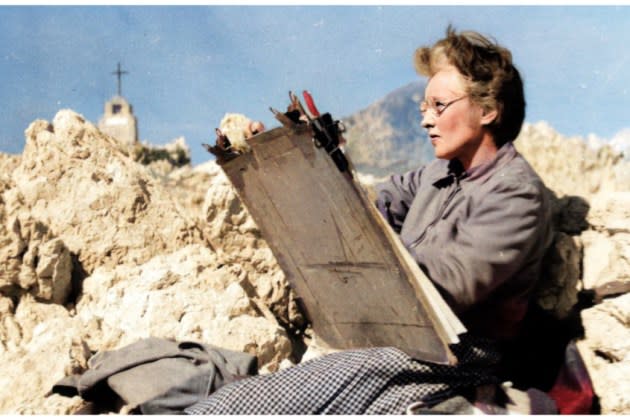

Not for the first time in his directorial career, Northern Irish documentarian Mark Cousins begins his latest work by presenting the audience with a mundane image and persuasively convincing us to reconsider it. The picture is an unremarkable holiday snapshot of 70- or 80-year-old British artist Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, dressed for a day of sightseeing in a sensible raincoat, projecting no particular halo of artistic genius . Cousins’ narrative ponders her position, her clothes, her casually comfortable aura, and wonders how easily these details make her—in a realm biased even against extraordinary women—overlooked. A triumphantly discursive, often lyrical valentine to Barns-Graham and her work, A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things aims to draw the eye to her angular modernist interpretations of nature at its most serene and stark, and train them to see the soul subversively expressed. there.

Premiering in main competition at the Karlovy Vary festival, where it won Christine Vachon’s top prize from the jury, this is among the most compelling documentaries to date from the prolific Cousins - bringing the same enthusiasm and empathy from artist to artist. which characterizes his film-focused work (especially his “Story of Film” series) to a fine arts subject that is not exactly a household name. Even this relative obscurity works in Cousins’ favor, though: “A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things” joins a recent wave of documentaries and dramas focusing on female artists previously neglected in popular culture (among them “Beyond Visible: Hilma af Klint, ” “Kusama: Infinity” and “Maudie”) in a collective effort to alter and expand a patriarchal canon. The film’s triumph at Karlovy Vary should generate plenty of additional festival bookings and specialist distribution across multiple platforms.

More from Variety

Anyone familiar with Cousins’ idiosyncratic films will know not to expect a standard biodoc of talking heads and archival editing. With the vocal assistance of Cousins’ regular collaborator Tilda Swinton, languidly reading various first-person passages from Barns-Graham’s letters and diaries, the film outlines the artist’s life story without copious biographical detail. We learn that she was born in St. Andrews, Scotland, from a landed gentry; that he studied at the Edinburgh College of Art; that he later settled in Cornwall, where he found both stage inspiration and a modernist artistic community; that he married once, unsuccessfully.

But Cousins is less interested in this kind of narrative than in a more abstract, sometimes speculative reflection on her aesthetic and spiritual fixations—pivoting on a formative 1949 trip to Grindelwald Glacier in Switzerland. There, she was mesmerized by the natural geometries of rock and ice, shapes and motifs that then permeated her work for the next half century. Such patterns and cross-lines in her drawings and paintings are made clear through the simplest of techniques: nefarious, mostly chronological, narrative-less slide show montages, accentuated only by Linda Buckley’s wonderful and thoughtful score, allowing viewers to digest and to silently respond to Barns- Graham’s art as in a gallery. Cousins does, however, take the liberty of speaking to us through her early notebooks: page after page of intricate color-coded, mathematically conceived compositions that reveal something of Barns-Graham’s synesthesia, a crucial factor in her art that it was both weakened and complicated by her growing fascination with the natural world.

As usual, Cousins is a critical figure in his own work, with the film built around his growing individual knowledge and affinity for Barns-Graham’s story. This builds on her own spearhead of a multi-screen installation dedicated to her work at Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket exhibition space, which again underlines Cousins’ sense of the permeable link between visual art and cinema. (“I wonder what David Lynch would make of this?” he says, looking at one of her darkest deconstructed glacier paintings.) Some art historians might debate Cousins’ claims about how marginalized was Barns-Graham in the popular view of 20th-century British art – she is on show at the Tate, although she was excluded from a successful Royal Academy exhibition dedicated to her contemporaries – but her film amounts to a compelling renewal of the work them in any case.

A certain degree of self-indulgence is par for the course – as in an interlude where the filmmaker gets a Barns-Graham painting tattooed on himself, wondering aloud how much it does or doesn’t bring him back – but not exactly inappropriate. “A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things” poignantly articulates how we can form deeply personal relationships with the artwork of people we’ve never met, celebrated or otherwise. This gives the film license for any number of unexpected angles – including a careful tangent, which could have even stood for greater expansion, on climate change and the physical disappearance of the landscapes that once inspired such abstract beauty. At one point, Cousins asks a biographer of Barns-Graham (who died aged 91 in 2004) if she would have welcomed a film about herself, only to be told that the artist probably wanted more to say in its content. No artist can control his legacy, so Cousins, in turn, invites us to read his moving and infectiously obsessive film as we will.

The best of the variety

Sign up for the Variety Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

#Glimpse #Deeper #Review #Great #British #Artists #Legacy #Unfrozen #Reexamined